The Return of the Triple Baka

An examination of vocal synth fandom through one song and three characters.

For a long time, it felt like the history of vocal synth was being forgotten. Hatsune Miku, the official mascot of the Vocaloid software (and the unofficial mascot of essentially all music made with voice synthesis), remained popular. She’s a recognizable presence in anime, music, visual art, and video game fandom, acting as a connective tissue for every disparate corner of otaku culture. She performed at Coachella. She’s in Fortnite. You can run your instrument through an effects pedal that makes your guitar sound like her. But there’s an entire supporting cast in the vocal synth universe that, as time marches on, has fallen out of the conversation. It’s not that the knowledge of these other characters has been lost—herculean community efforts like the Vocaloid Database and Vocaloid, UTAU, and SynthV wikis have more information about obscure characters and voicebanks than you could read in a lifetime—but they were simply not capturing the interest of younger creative people developing new interest in vocal synth.

On July 13th, 2008, vocal synth producer LamazeP published the song “Triple Baka,” along with an accompanying music video he animated himself. Joining Miku are two other characters, coded red and yellow, complementing Miku’s pale blue motif with a triumvirate of primary colors. The upbeat denpa-inspired song would prove popular on Japanese streaming site Niconico (formerly Nico Nico Douga), becoming an early viral vocal synth hit and helping to popularize the two virtual idols flanking Miku on either side. But who are they? Kasane Teto and Akita Neru, conceived as parodies of Miku, have similar but distinct origin stories. Until fairly recently, it felt like “Triple Baka” would be the peak of their respective popularities—but both of them have managed, against long odds, to make what seemed like an impossible comeback. Tracing the mythology of each member of the trio individually, a pretty solid record of vocal synth fandom starts to take shape. So starting from least to most obscure, let’s examine the history of the Triple Baka.

Hatsune Miku

In 2004, the first Vocaloid program was released by Yamaha. It’s a vocal synthesizer software that could convert lyrics and melodic input into “singing” via pre-configured voicebanks. Like existing speech synthesis software of the time (think classic Microsoft Sam), recorded voices from a real person are used as a model to develop a virtual singer. The earliest Vocaloid voicebanks, Leon and Lola, were only compatible with English speech and their voice providers are still unknown. It was an interesting but niche piece of software that was only used by a limited number of digital music enthusiasts.

Then, in 2007, everything changed. Yamaha partner Crypton Future Media, who were already in the business of creating sound libraries and BGM collections, internally developed their own voicebank for the improved Vocaloid 2. Their original character, Hatsune Miku, wasn’t just a disembodied voice like previous iterations. They commissioned the famous voice actress Saki Fujita to provide vocals, and manga artist Kei Garo created an illustration of an android pop idol with flowing blue hair. She immediately resonated with bedroom producers and visual artists alike; they created new works and shared them on Nico Nico Douga, which launched only the year prior. It was the frontier of a new fandom, using new technology, being distributed on a new platform.

The marriage of music and visual was always an important aspect of vocal synth. Supercell, one of the first breakout Vocaloid artists, uploaded their first single “Melt” to NND featuring a striking original illustration of Miku by the artist 119—used without permission. Following the unexpected popularity of the song, ryo (the producer for Supercell), messaged 119 to apologize for grabbing their art without asking. From then on, a partnership was formed and Supercell became a collective of artists and producers. As Vocaloid started to gain international attention and spread to sites like YouTube, that culture persisted. (Morii Kenshirou, a flash animator who made a name for himself providing visuals for Vocaloid songs by siinamota, 40mp, and DECO*27, would go to work on mainstream anime productions like Fullmetal Alchemist.)

Crypton would continue to push Miku as the face of their flagship product, but they didn’t have to market her very aggressively; creative folks naturally wanted to use her as an avatar for their projects due to her lack of any canon characteristics. She had a stated age of sixteen, but it was also encouraged that she could be aged up or down. She doesn’t have any lore to speak of, either. Miku would become almost like a folk hero, malleable and able to transform into whatever best suits the expression of the person telling her story. This flexibility would ultimately extend to other vocal synth characters, with the most common recurring themes being decided by the fandom and, in some cases, acknowledged in a more “official” capacity. (The famous depiction of her holding a green onion, for example, comes from a fan cover of the Finnish song “Ievan Polkka” in which she’s drawn waving around a vegetable.) She’s whatever you need her to be.

Kasane Teto

Teto was conceptualized as an April fools prank by users of the Japanese 2channel message board in 2008. In response to Miku’s rapid ascent, a spoof of her design was created to trick Vocaloid fans into believing a new character was coming. Teto bears a strong resemblance to Miku (her clothes, especially, are almost identical) but the iconic aqua color scheme was swapped out for a deep red and the long twintails were replaced by a pair of tightly coiled ringlets. A “04” tattoo adorned her left shoulder, referencing what would have been her status as Crypton Future Media’s fourth character in the Vocaloid series. (Miku is 01, the twins Kagamine Rin and Len are 02, and Megurine Luka is 03.) Later iterations of her design have changed this to “0401,” or April 1st—the date of her birth. She was given a voice, provided by Mayo Oyamano. Her “official” art, illustrated by Sen (線), was close enough to Crypton’s early Miku art to fool enough people.

Despite never being intended to be anything other than a joke, interest in Teto persisted and she started acquiring genuine fans. Her voice was recorded again to make a voicebank in the shareware vocal synth software UTAU, and producers immediately got to work making original songs. (One of these early songs, “Kasane Territory,” poked a little fun at the fact that Miku’s voicebank would set you back nearly 16,000 yen while Teto was free for everyone.) A doujin circle called TWINDRILL was even created to manage and market the character.

Teto would receive nods of official acknowledgement here and there, but it was mostly nothing substantial. She was added into the Project Diva 2nd rhythm game, but only as a cosmetic skin. You could see her singing and dancing, but the voice coming out of her mouth was still Miku’s. (Fans on Nico Nico Douga and YouTube would create cover versions of songs in Project Diva with Teto’s voice and pair them with visuals from the game so it almost felt like the real thing.) Wataru Sasaki, the engineer who created Hatsune Miku’s voice in Vocaloid, tried his hand at replicating Teto for the official software in 2012, but couldn’t get it right and the project was scrapped.

It wasn’t until 2023, when Oyamano was tapped to record new vocals for Synthesizer V Studio, that Teto finally received an air of legitimacy. Alongside this voicebank for the Vocaloid competitor software, Teto received a refreshed design that did away with her references to Miku. Finally, she looked like herself. Similar to UTAU, SynthV is more accessible than Vocaloid with a variety of cheaper options and free voicebanks. Unlike UTAU, though, it’s much easier to use. This combination of increased visibility for Teto and easier software to get your head around led to an explosion in popularity. Younger producers that were less attached to Miku were particularly charmed by her. For the first time, some of the most ubiquitous vocal synth songs featured Teto (both instead of and in addition to Miku). In a surprising reversal, one of the Teto’s biggest recent songs, “Tetoris,” was being covered by Miku instead of the other way around—and the Vocaloid poster child’s version was far less popular.

Akita Neru

Whereas Teto was conceived as a bit of fun, Neru was born from a conspiracy theory that got out of hand. In late 2007, as Vocaloid was quickly spreading throughout the Japanese internet, it was enough of a phenomenon that television programs were running stories about the new cultural sensation. One characterized the Miku faithful as “jobless anime freaks,” which didn’t sit well with the nerds on 2chan. In the coming days after this negative piece, images of Miku disappeared from Google search results and the Japanese language Wikipedia page for the fictional idol disappeared. Naturally, netizens figured, this must have been the work of a shadowy agency actively coordinating to erase an emerging otaku trend from existence.

Speculation about why someone might want to quietly delete Miku raged on the message board for days, and of course, the threads attracted the attention of people that just wanted to troll. A deluge of messages with some variation of the phrase 「飽きた、寝る」(TL: I’m bored, going to sleep) appeared, which the channers dismissed as agitators on sock puppet accounts. Eventually, it would surface that the search results were a temporary server-side error and the Wikipedia page was removed due to a claim over copyrighted assets. Still, the timing seemed suspicious and some people continued believing there was a real anti-Miku mafia.

Inspired by this bizarre flare-up, illustrator Smith Hioka designed an inverted Miku persona. Her outfit resembles her counterpart, though her accent color is a bright yellow. Her hair is fashioned into one long side ponytail instead of two. In place of Miku’s friendly demeanor, Neru’s face is twisted into a permanent scowl and she’s brandishing two cell phones—one clutched tightly in her hand and the other in a holster on her thigh—that she uses to make hateful posts about Miku at all hours of the day. She would be named Akita Neru (亞北ネル), which reads phonetically identical to the message being spammed by the Miku-hating trolls.

Neru gained a modest following as a fanloid in the following years, being used as the subject of songs and music videos despite not having a voicebank of her own. Generally, when someone makes a “Neru” song, it’s just Hatsune Miku’s voice—sometimes unaltered, sometimes pitched up an octave. More rarely, it can also be Kagamine Rin pitched down. Similar to Teto, Neru would receive some minor acknowledgement from Crypton in the form of Project Diva cosmetic DLC, which Hioka says he got the opportunity to design himself.

In early January of 2025, producer Hiiragi Magnetite created a song called “Zaako” with the Vocaloid Kaai Yuki as a voicebank. The song attracted a bit of controversy due to the choice of character, with some insisting she was the wrong choice for such a suggestive song because her voice provider was only a fourth grader. Hiiragi quickly pulled the song and set to work “fixing” it, surprising the vocal synth community a month later by replacing the voicebank and having the artist reanimate the entire music video with Akita Neru. Notably, there's a segment where Miku and Teto appear alongside her and Vocaloid fans went insane. 17 years later, the Triple Baka are finally back together. ✿

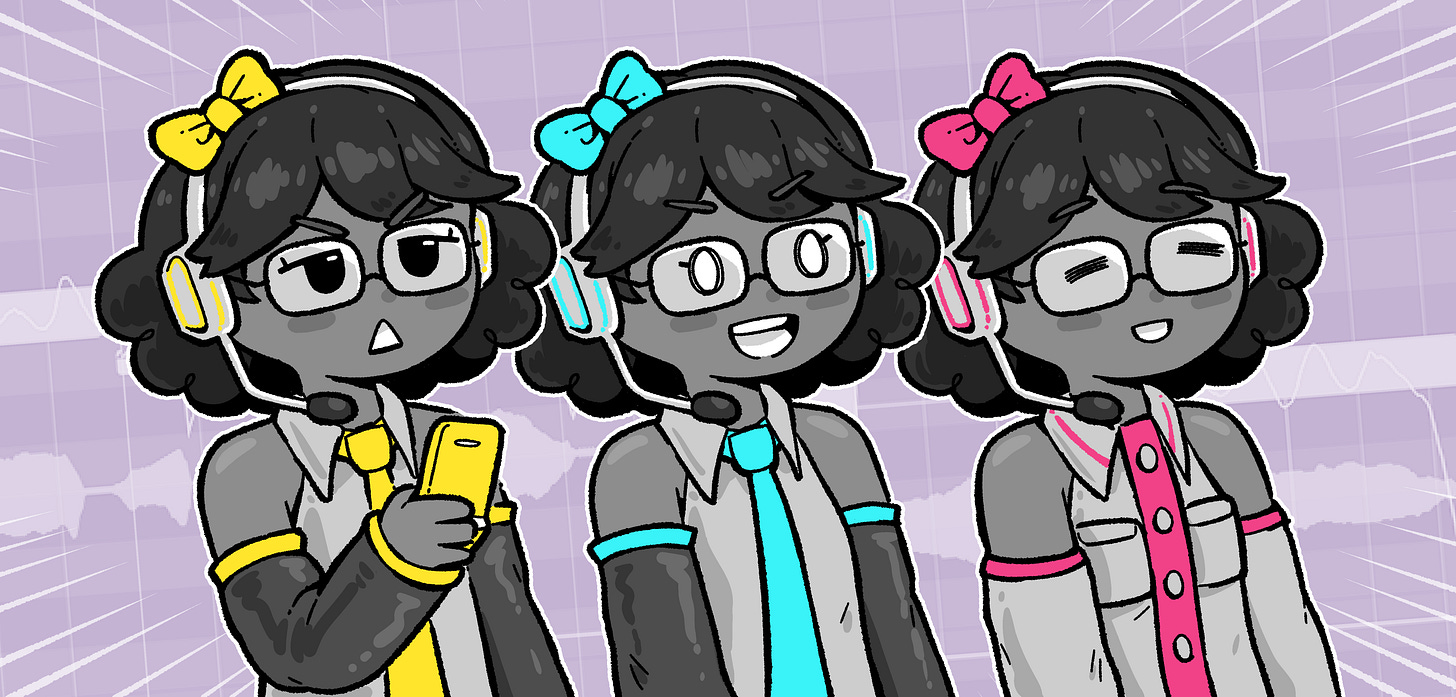

Thanks for reading this thirteenth installment of once bitten, twice shy. Wow. I love Vocaloid. Go follow my brilliant oomfie william_ leonard, who drew the incredible header image and makes really cute comics.

If you appreciate the newsletter and want more needlessly in-depth vocal synth history, consider hitting the Ko-fi link and donating. I’m trying to get all my ideas out while I am motivated and having fun writing again. So far so good!

Okay I love you byeeee. 💛💙❤️

I knew about Miku and Teto's history but not Neru's! Wild read, honestly, specially Neru's section!!

Thank you!! Very cool