On the move: the story of Tokyo Mobile Music I

Demystifying the compilation that introduced me to Japanese new wave music.

Compilations were the backbone of my musical education. When I wanted to get into a genre but didn’t have the slightest clue where to start, it was always a safe bet to trust the judgment of someone who cared enough to put together a primer for you. Before the advent of sprawling genre or “vibe” playlists on platforms and Spotify and YouTube—at first curated by real humans, though rarely the case these days—collections of related music had to be assembled by people that knew their stuff. As a kid, I would often see a series called Hard to Find 45s on CD populating the bargain bins of department stores and the seldom-disturbed CD racks in thrift shops. Each disc would focus on a narrow period of time in pop music history (sometimes as vague as “the ‘60s” or as specific as “1957-1959”), with liner notes providing some quick facts about each artist featured.

The More Sixties Classics edition was the first one I purchased, and I was surprised to find a lengthy essay inside by music historian Greg Adams which laid out the mission statement for the series. The parent label, Eric Records, was founded in 1986 on the conception that it would only publish 45 RPM singles of oldies pop hits, with the intention of keeping them available in perpetuity. When the arrival of the compact disc pushed vinyl record players out of American homes, the label needed a new strategy—and so they started publishing their vast catalog of yesteryear’s songs on CD compilations, keeping them accessible and affordable. At a glance, these compilations look like cheap junk. It’s entirely likely you’ve glossed over them in record shops, their unassuming and near-identical covers making them invisible to your eye. But these things were the backbone of oldies stations; if you ever heard a disc jockey spin “Look for a Star” by the late ’50s crooner Garry Miles, there’s a high likelihood it was one of these discs in the console.

For international music, especially before the internet was as accessible and populated with information as it is today, a well-curated compilation was especially important. Labels like Sublime Frequencies completely transformed my idea of music from the Eastern Hemisphere, and I’m not sure I’d have even a passing interest in North African music if not for the anthologies Sahel Sounds put together. My strongest enduring interest is in Japanese new wave, though my introduction to it was strange. In my teenage years, on a blog I’ve long forgotten the name of, I found a curious little omnibus called Tokyo Mobile Music I. It’s sort of the total antithesis of a useful compilation for getting you up to speed about something brand new to you.

Let’s have a look at the liner notes, which is only three sentences:

Collating the tracks for this album has not proved to be the easiest of tasks. However I hope these tracks will serve as a foretaste of what is to come from Japan in the future. The Mobile Suit Corporation will be focusing on the East and unearthing as much new talent as possible.

—David Claridge

It says nothing about the artists comprising the tracklist and peddles a promise of prospective importance rather than attempting to illustrate a cohesive picture of an existing scene. I’m not sure why I should trust Mr. Claridge to be the guy to surface new talent from Japan, either. So who is he?

David Claridge is best known as the creator and puppeteer of Roland Rat—a name unlikely to ring a bell to most, but if you were a wee lad or lassie in the UK in the 1980s he was a bigger deal than even Kermit the Frog. Unlike his most comparable peer in the industry of puppetry, Jim Henson, Claridge stayed out of the public eye and let his rascally rodent friend do most of the talking. He kept public appearances to a minimum and scarcely did interviews, seeming content to focus on his craft.

A scant few details about him do exist, mostly about his activities outside of puppeteering. As a young kid he immersed himself in theater, studying mime arts and stage acting from the age of 12. After moving from Birmingham to London he became fascinated with the local club circuit in the late ’70s, right around the peak of the New Romantic movement. It seemed like a logical fit for someone with an interest in the performing arts; the style and attitude of the emerging scene drew heavily from the aesthetics of cabaret and commedia dell’arte. He became a regular at Blitz, the nightclub considered ground zero for the New Romantics, until its closure in 1981.

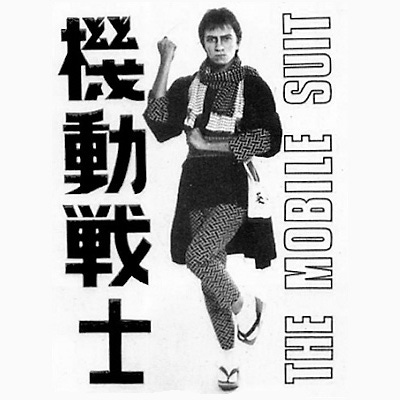

Claridge tried to fill the void by planting his roots at other clubs, but eventually grew bored of the New Romantic milieu. He felt it had adopted the problems that led to its creation as a counterweight to punk culture: it had become stale and predictable. His desire to create something new was partially inspired by a burgeoning interest in Japanese music, which he said in an interview for a local magazine was setting his mind alight with new possibilities. Unsatisfied with the state of London nightlife, he created his own roving club experience called The Mobile Suit, combining Japanese costuming with imported music from their fast developing new wave scene. He toured The Mobile Suit around the country, to modest success. (Interestingly, Claridge’s nomadic troupe is still remembered fondly among fetish enthusiasts.)

Seeing an opportunity to introduce Britons to music from what he called the “Far East,” he worked with major label Phonogram to create an imprint called The Mobile Suit Corporation aimed at highlighting his latest obsession. The label would ultimately not amount to much before he abandoned the venture to return to puppets; the bulk of its output would be a single LP and a set of supporting singles for the Indian-themed group Monsoon. There was, at least, one honest attempt at seeing his vision through: Tokyo Mobile Music I, a compilation of the new music from Japan that Claridge found to be most forward-thinking.

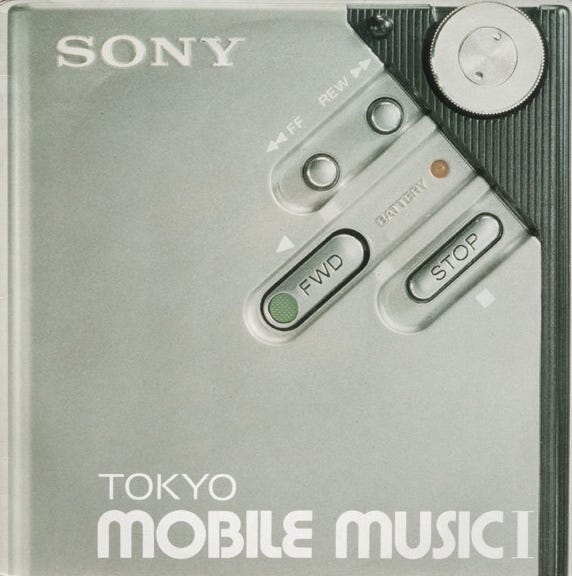

Because there are no liner notes to speak of, it’s not clear why Claridge selected this particular collection of songs. If I had to guess, these are the records he encountered in his personal explorations around Tokyo. The only documentation of his travels are the short field recordings between songs, taped on his handheld Sony Walkman pictured on the album cover. They’re an audible travelogue of him hopping on and off public transit, skulking around in stores, and eavesdropping on people making orders at a Shibuya McDonald’s. It also seems that he had every intention to make it a series of releases, given the title bears a roman numeral, but there would only ever be the first installment.

The lack of any useful information about the artists herein fascinated me as a curious listener that had never heard anything like any of these tracks before. Tokyo Mobile Music I is an incomplete picture, compiled by an amateur that was only just beginning to grasp what he was seeing. I had to do a lot of my own legwork to learn about these artists and understand where they fit into the history of Japanese music, so I’ve taken the liberty to write some liner notes for this release myself. I hope they’ll be a good jumping point to find some new music you love.

Hikashu

If Yellow Magic Orchestra is patient zero of Japanese new wave, Hikashu was hot on their heels. The band would reinvent themselves a fair few times in their career, flirting with prog, jazz fusion, and melancholic darkwave—but by the release of Tokyo Mobile Music I only had a couple albums to their name. I don’t think it would be too derisive to call their early output pretty straight-ahead Kraftwerk worship, especially considering one of the two songs they contribute to the compilation is a cover of the German group’s biggest hit “The Model.” Vocalist Makigami Koichi, with a vocal style inspired by Kabuki theater, gives the Japanese language rendition a bit of unique texture. The other track, “New Tribe” comes from their 1981 album うわさの人類 (Uwasa No Jinrui, TL: The Legend of Humanity), which marks the beginning of their more experimental pivot.

Akiko Yano

Also represented by two tracks, both from her art-pop masterpiece ただいま。(Tadaima, TL: I’m home), is Akiko Yano. She studied jazz piano in high school, became a sought-after studio mercenary shortly after graduating, and before her 21st birthday had begun work on her first studio album. Through industry connections she met her one-time life partner and lifetime musical partner of Ryuichi Sakamoto, who produced Tadaima. and supported her with writing and arrangements. The standout track is “Rose Garden,” which seems to have just about every sound a well-equipped studio can make—wobbling bass, thumping taiko drums, and quivering vocoded voice like a wounded animal heard through a high-speed oscillating fan.

Earthling

Earthling might be the most difficult artist on Tokyo Mobile Music to find any information about. The short-lived dance punk trio was Jin Haijima on vocals and lead guitar, Yoko Fujiwara on bass, and a man credited mononymously as John on the keys. John and Yoko (no, not those) were textile and fashion designers before starting a band together, and presumably went back to their careers after putting out two records in ’81 and ’82. “You Go on Natural” appears on both albums, as a studio cut on their debut Dance and as a live recording on the follow-up Rhythm. For whatever reason, Claridge decided to pick the live version here, but I think it’s the right choice; the song’s a bit one-note but the sounds of a crowd coming alive give it a much-needed energy infusion.

Yukihiro Takahashi

Takahashi probably needs the least introduction of any artist featured here, but nevertheless: he was one third of the internationally treasured Yellow Magic Orchestra—the group’s percussionist, occasional vocalist, and writer of songs like “Rydeen” and “Ballet.” Of the three, Takahashi’s interest in new wave was the strongest. He would go out of his way to form working relationships with English musicians, eventually flying to London to record with many of his New Romantic heroes on 1981’s Neuromantic. But before he had the opportunity to work with musicians from Roxy Music, he was content to simply imitate them; on “Mirrormanic,” from his second album Murdered by the Music, he digs deep to give his best version of Bryan Ferry.

Shoukichi Kina & Champloose

It’s easy to feel like Tokyo is all that matters in the landscape of Japanese popular music, but so much is owed to people that have been pushed to the fringes. Shoukichi Kina, from the southernmost Okinawa Prefecture, insists on putting his culture front and center. He performs Okinawan folk standards alongside songs he’s written himself, and though he’s a proficient guitar player also makes frequent use of an electrified sanshin—the indigenous instrument of the Ryukyuan people that, through a century of iteration, became the shamisen in mainland Japan. Featured here is “ミミチリ坊主” (Mimichiri Bozu, TL: ear-cutting monk) an Okinawan traditional song meant as a lullaby for children. The mimichiri bozu is a yōkai that threatens to lop off the ears of young boys if they stay up past their bedtime. Eek!

Lizard

Claridge writes that the artists featured offer a “foretaste of what is to come from Japan,” but Lizard has the distinction of being the one act whose story appeared to be over. Originally formed in 1972 under the name 紅蜥蜴 (Benitokage, TL: Crimson Lizard), the band put out a series of lo-fi 7” singles recorded in dingy live houses. Influenced by glam rock, the group gradually transformed as English punk started to wash up on Japanese shores. By 1978, when they rebranded as “Lizard,” they were on the frontlines of Japan’s nascent punk scene. The group disbanded in 1982 due to their frontman, Momoyo, being incarcerated on drug charges. He wouldn’t sit in the slammer for long, but the experience seems to have scared him straight; Lizard would remain dormant for four more years and would only release one more album and an EP before calling it quits for good. The song featured here is “SA・KA・NA,” which Lizard recorded on several occasions. This is an especially obscure version from a 1980 single labeled “Disco Style,” though it sounds more like ska than anything else.

Salon Music

Credit to David Claridge: in at least one instance, he really did put his money where his mouth was. New wave rockers Salon Music would go on to have a long career and put out twelve albums, but by this point in 1982 had yet to put out their first. The first song they ever released, “Hunting in Paris,” debuts here in a rough early form. The Mobile Suit Corporation, the sublabel Claridge created under Phonogram (where he did A&R work), also pressed a split single of “Hunting in Paris” alongside Lizard’s “SA・KA・NA” on the B-side. Salon Music would polish up the song and record it again for their inaugural record My Girl Friday, but their scrappy beginnings can be heard on Tokyo Mobile Music I.

Thanks for reading this fifteenth installment of once bitten, twice shy. Having a good 2026 so far? Good. Me neither.

I’ll be making a serious push to publish at least two things a months from here on out. If you like the newsletter and consider it worth your while, I’d ask you to consider making a donation on Ko-fi! There’s an option for a recurring monthly donation, which would really help me maintain this thing in something more resembling a full-time capacity. I will work hard to make sure it’s worth it for you!

Okay, see you next time. Byeee. 💜

👍 👍 Do you have a Spotify pl for this article? I'd like to check it out if so, tia!