Tokyo Loop

Sixteen reviews (by ten writers) of independent animated films from the Image Forum's 2006 festival.

Collaboration is usually just an excuse to get things done. When you commit to doing something with one or more people, the benefits are immediate. You’ve got someone to bounce ideas off. Someone’s there to hold you to account if you start slacking. You get to see the amazing things your peers are capable of, giving you motivation to elevate what you bring to the project. I’ve always romanticized the idea of an “art collective” in which I’m locked in a creative contract with like-minded friends, buoying one another and pushing the group to new imaginative heights. In theory, it sounds like a great shortcut; in practice, creative endeavors are still difficult. You still have to give them your all.

Tokyo’s Image Forum, which puts together yearly festivals for experimental art and film, is tough work. Under the guidance of the program’s director Takashi Sawa and coordinator Koyo Yamashita, a group of intrepid filmmakers is assembled and given a prompt to start with. In 2006, Stuart Blackton’s Humorous Phases of Funny Faces—the first publicly screened animated film—was nearing its hundredth anniversary. The Image Forum, looking to celebrate the occasion, sought out independent animators for that year’s festival. The theme provided was “life in the city of Tokyo”—which is, of course, intentionally vague. It’s simply a germ ideas can begin to multiply from.

Another common thread is that every film features music by Seiichi Yamamoto, a legend of Osaka’s underground scene and the guitarist from the band Boredoms. (Their album Pop Tatari, by the way, is one of the all-time greatest.) Yamamoto composed for the films before even seeing them, using sketches and storyboards as his guide before making minor adjustments for the finished cut. The filmmakers had a chance to respond to Yamamoto’s score, which took inspiration from their unfinished idea. It was a uniquely collaborative process; Yamamoto got to see sixteen different people work in vastly different ways and solve unique problems with each of them.

When I approached several friends to help me cover the Tokyo Loop anthology, I had a similar privilege to see a window into their minds. My instructions were also vague: write about your assigned film however you feel compelled to. Some chose to research the filmmaker; some chose to tell personal anecdotes; some chose to speak in images; some chose to be silly. I’m grateful to all of them for their contributions. Below, you’ll find reviews of each film by me or one of my pals. What we’ve put together is a fascinating survey of Japanese independent animation—but more importantly for me, it was a good reason to do something with people whose thoughts I love to hear.

Tokyo Loop is available in full on Archive. I encourage you to watch every film. They’re all only five minutes at most! —Shy Clara Thompson

Unbalance (dir. Takashi Ito)

Takashi Ito was disturbed while making Unbalance. In his description for the film, he explains that this work is a reflection of his thoughts on Tokyo, meant to portray “the emotional state of people struggling and suffering in this very superficial world.” This isn't new territory for the avant-garde filmmaker, as his shorts have always been defined by their uneasy atmosphere. His goals, really, have remained consistent: with 1982’s Thunder, he longed to “depict the disgust and beauty of the human body collapsing,” he relayed in a 2009 interview. Such grotesqueries are never presented as mere shock-value; instead, Ito’s films are a result of identifiably patient methodologies, utilizing pixilation and long exposure to capture life as a spectral haze.

Unbalance begins with this same unsettling air: a human face presses through a white sheet, his mouth opening wide as if screaming for help. No diegetic sound appears, leaving our understanding of his pain incomplete. Soon, the image dissipates in flames. Ito soon grounds this abstract imagery in the real world: a cut reveals an unfurling hand and then a man’s face, but even though his body is uncovered this time, his worried demeanor communicates uncertainty. A time-lapse shot of moving clouds is juxtaposed with his wandering eyes, as if he is watching the world move on without him. Soon, his back faces the camera and his head is face down; the tone is ominous, and his haunted presence is like one from a 1990s J-horror. When movement does arrive, it does so with his sudden collapse onto the ground. The remainder of the film largely shows him struggling to stand, wrestling with another body, and his face getting distorted: this isn’t forward momentum, just frustrated spasms.

Ito opts for more jittery motions and edits as Unbalance progresses. With rephotography, he pans the image so that we move outside its frame, and the resulting effect is uncanny: we feel the claustrophobic nature of this man’s situation, as if he is stuck within the confines of this filmic space, but there is also a longing for total release. When we watch him struggling in a hallway, it is akin to voyeuristically watching CCTV footage of someone in a psychiatric hospital. There are cuts to a pitch-black space, too, which bridge the realism back to the metaphorical, symbolizing his mental breakdown. The soundtrack proves caustic, as it is little more than blaring, intermittent noise. The cacophony, provided by Boredoms guitarist Seiichi Yamamoto, doesn’t correspond to any of the edits, and instead provides another point of disjuncture to feel detached. It is an “intense reality” that Ito always longs for viewers to experience. And with Unbalance, he is able to make numbness palpable. —Joshua Minsoo Kim

Fig (dir. Koji Yamamura)

Koji Yamamura’s dreamlike style draws heavily from Soviet cartoonists like Priit Pärn and Yuri Norstein, as well as the pioneer of motion photography Eadweard Muybridge, and the admixture of these potent influences refuses easy interpretation or categorization. Yamamura centers Fig on a man with a block-shaped head, with Tokyo Tower serving as his nose. Our protagonist’s reality-warping melancholy pairs well with Seiichi Yamamoto’s melodramatic jazz soundtrack, but the visceral qualities of Yamamura’s usage of sound shines through the short continually. From the wet slap of the protagonist flicking a clump of his own tears through a powerline, to the sound of a bird’s wings flapping, to the soothing pour of water from the head of the titular fig towards the end, Yamamura uses these evocative sounds to anchor us as we’re set along a flowing river of rhyming images that keep the viewer on their toes.

At the end of the short we see a breathtaking shot where a lightbulb is shown to shatter, with the shading inside of it falling out to become the fig as it lands on a table below. As the man departs into the sky, and the sun rises over Tokyo, we see the tower now in the distance, a plate of figs on the table in the foreground. Yamamura conjures this quiet, lonely scenario with such a warmth, aided by the soft guitar of Yamamoto’s second track, and I’m brought back to the solitary days I’ve spent during the pandemic, watching the sun rise as I missed the life I had before. Fig’s fable-like story of a depressed man wearing one of Tokyo’s most iconic figures on his face incorporates his myriad influences into a beautifully strange and deeply affecting work that soothed my solitude and made me feel less alone. Though his style changes often, his ability to make one feel understood in their madness makes him a powerful director. —Ryan Waller

Tokyo Trip (dir. Keiichi Tanaami)

Keiichi Tanaami is one of Japan’s first pop artists. Inspired by the multimedia approach of Andy Warhol, he told visual stories of Japanese life in bold color—not only in the visual arts, but through animation and film too. Tanaami’s early forays into filmmaking borrowed heavily from American iconography, rendering images of recognizable faces like John Lennon and Marilyn Monroe alongside realistic cutouts of consumer products and still images from pornography. Over time, Tanaami would move away from American imagery and turn inward, basing more of his artwork on childhood memories and scenes that came to him in dreams. With a shift in subject matter came changes in style; occasionally, the striking blocks of primary colors would be absent, giving way to looser works in pen and pencil that lacked the visual clarity Tanaami became known for.

Tokyo Trip strings together a series of scenes that, superficially, don’t seem related to one another at all. An eyeball perched atop four legs sprints at full speed, then slows to a brisk walk; a train with a goblinesque face speeds along a set of tracks, picking up so much momentum that its ghastly visage is obscured by motion; a gangly hand grasps onto what appears to be a teru teru bōzu while rain pours down in an unending torrent. Each little tableau only lasts a few seconds before moving on to the next, animated only by a handful of oscillating frames. You’re given a scant few clues about what's unfolding in front of you, mostly in the suggestion of directional motion. Tokyo Trip is the most similar film in the collection to Humorous Phases of Funny Faces—the film Tokyo Loop is commemorating—especially in its rudimentary animation techniques. Distorted humanoid forms and exaggerated motion tell a nonlinear tale of, presumably, a version of Tokyo that exists below the surface of Tanaami’s own consciousness. It was as if he’s trying to capture the inscrutable logic of dreams. —Shy Clara Thompson

Public Convenience (dir. Tabaimo)

I hate public restrooms.

I hate them because when I am in one, I feel like I understand too much. They are containers for the reality of us; try as we might to cover it all up with aerosol and fans and stalls to hide us away, we still run to them to shit and cry and expel our shame. They are places of gossip and crime and heartbreak and sex—our private truths laid bare in a room we all gather together in to convince ourselves we are alone. We do our business while ignoring others and wash our hands and leave and pretend that nothing at all happened.

But something did. Something is always happening. None of us can ever really leave the restroom.

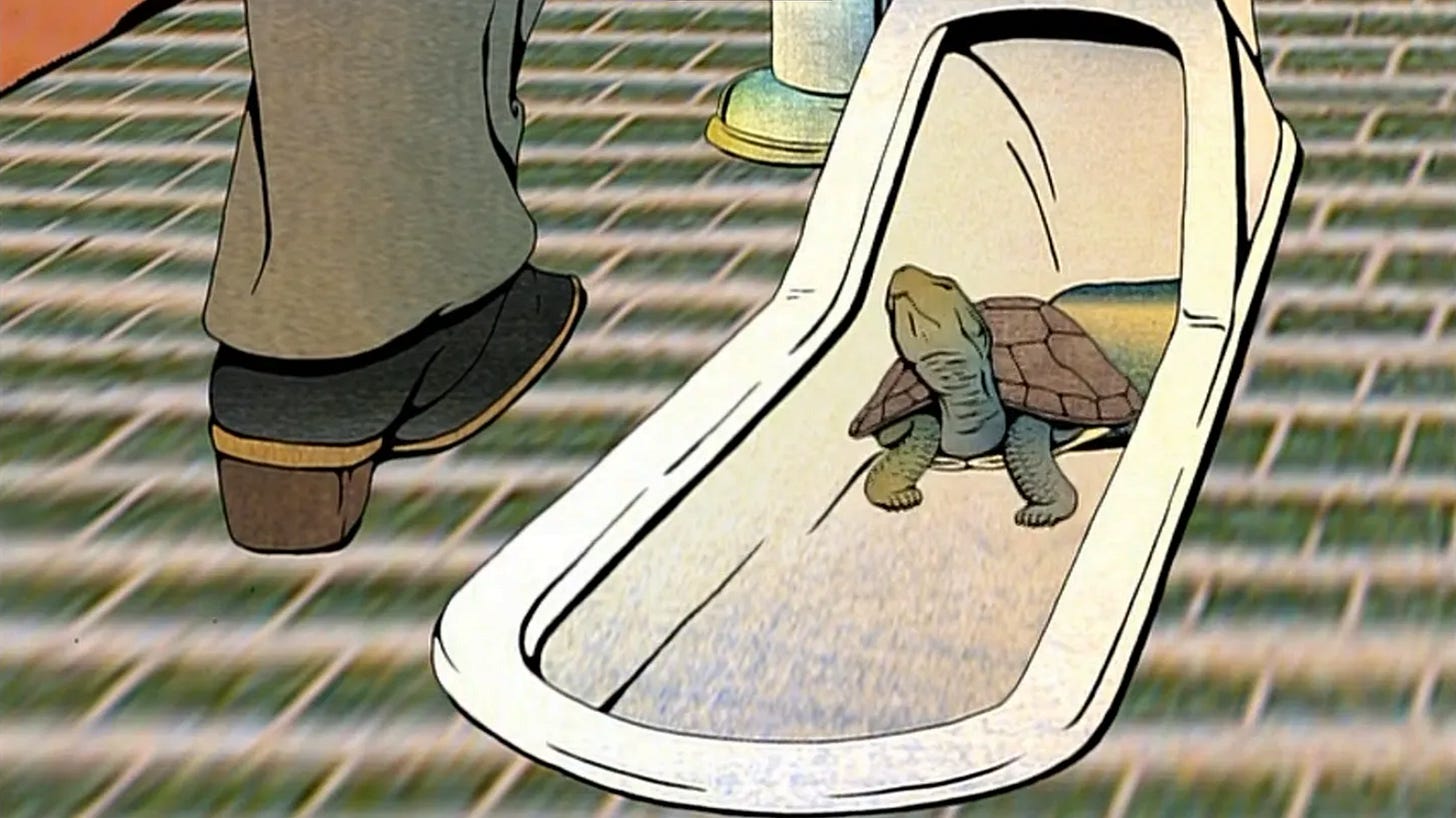

Artist Tabaimo’s short film, Public Convenience, takes place in a public restroom. It’s full of filth. The film operates with a rhythmic repetition, animated characters reenacting the same actions as if on a loop while women’s voices hum and glitch and break down in the background. In one stall, a woman tries again and again to flush a turtle. In another, a newborn baby wrapped up in a plastic bag. Someone walks up to the sink, looks at herself, and breaks the mirror. A bird with camera eyes spies on them all. Watching this animated menagerie is to watch the world become a cartoon, turn unreal.

That’s how it always is in a restroom. And that’s how it always is online.

“There’s an interesting similarity,” Tabaimo says in an interview for Modern Museet about the film, “between public lavatories and the internet… The same anonymity exists.”

She’s right. The internet is exactly the same. Given any illusion of anonymity, we write on the walls and shit on the floor. We let our insides spill out of every pore of our body, all of the awful things we don’t want the world to see. After all, it is a place for gossip invented and real, a place for desperate blogs and tweets and DMs; a place for image boards that celebrate school shooters and forums dedicated to driving strangers to suicide.

And like a restroom, the privacy is an illusion, the anonymity a lie. If anyone opens their eyes and looks, they can see you. They can know who you are. And yet, we have been trained to believe we are alone so well that our outsides have begun to fade, our features disappear. We let everything turn into a cartoon, safe and separate from reality.

Public Convenience ends with a woman looking into the mirrors, then leaving the restroom. The camera does not follow. It sits on those mirrors, one broken, as they reflect back the restroom. They reflect back us. They reflect back nothing. —Baxter

TOKYO (dir. Atsuko Uda)

Atsuko Uda cheekily wraps the title of her contribution to Tokyo Loop in the infamous HTML <blink> tag which, if it were a webpage, would cause the words contained within to flash in and out of existence much like the neon signs that TOKYO uses as muse. <blink> allowed for the breath of life, a kind of crude animation, into the mostly static web pages of the early web. I've always been fascinated by cinema that makes commentary on the nature of the form as a kind of light show, calling attention to the rapid flashing of images that create the sensation of movement.

There is the genre of flicker films, or, for a more gentle example, Nathaniel Dorsky's recent aperture experiments in which he stops his camera down till the image darkens before opening the lens up again, creating the sensation of an eyelid blinking. But this is not just a game for avant-garde cinema, Stephen Spielberg's Close Encounters of the Third Kind both worships and fears light, a holy fire equally salvific and destructive. In TOKYO, light often takes the form of baubles—glowing, blinking orbs—overlaid on simple shapes to create the illusion of movement, not so much in the usual cinematic form but more like advertising signs that animate their subjects by rapidly switching on and off certain parts of the image to create an illusion of motion. TOKYO's Tokyo is a literal city of lights, the world rewritten in the lexicon of commercial light, those signs which beckon adventures within.

The film imposes a psychedelic overlay over a bus's traversal, which recreates the natural and urban landscapes of Tokyo, distilled to postcard iconicity, by way of gently looping blinks that culminates with the city as simultaneous kaleidoscope. Uda allows the viewer to read the city as a film: a series of flickering lights filtered through the windows of a bus create a hypermodern landscape penned in a neon language. —malaphorically

Black Fish (dir. Nobuhiro Aihara)

Aihara was an experienced and versatile animator whose work graced many commercially renowned and successful anime, from Galaxy Express 999 to Gauche the Cellist, but the bulk of his legacy lays with his trailblazing independent work, of which Black Fish is a strong example. Black Fish revolves around a surging maelstrom of colors that pulse and flow with a musical intensity. The beginning of the film, with its surging heavy color obscured by massive swathes of black, combines with Seiichi Yamamoto’s soothing ambient soundtrack. It’s as if Aihara juxtaposed a thousand paintings from the South Korean Dansaekhwa abstract art movement on top of each other, rapidly cycling through dense expanses of color. Eventually, the view pulls back and we see faces and twisted fish emerge from the writhing mass, before we dive back into the depths. It’s mystifying, relaxing, and a beautiful demonstration of the possibilities of the moving image.

Aihara’s career is so fascinating because even though he’s got a strong history working on mainstream anime, much of what he’s remembered for is his experimental work. He was famously protective over his personal, experimental shorts, rarely allowing them to screen when he was alive. Getting to watch Black Fish feels like being let into the secret, rich inner world of an artist who dedicated his life to exploring form in its purest manifestation. —Ryan Waller

Tokyo Strut (dir. Masahiko Sato, Mio Ueta)

Before you even see a single thing in Tokyo Strut, you hear this incredibly drum heavy track kick in. It’s so rhythmic and it just makes you wanna dance. That’s because Tokyo Strut is telling you that the main star of this movie is the music.

Don’t misunderstand me though, the visuals are incredible. The first thing you see is a set of stationary dots moving but your brain doesn’t interpret them as isolated circles. Instead it’s as if you’re looking at a person and a dog, right down to the momentum of them swinging their limbs. This is really difficult to put into words, maybe more so than any other film I’ve seen, so I’ve created a .gif to capture this moment.

Do you see what I mean? There clearly isn’t a dog and a human walking here but your brain somehow manages to recognise them anyway. And to me, this technique really captures what makes film such an interesting medium.

In film, everything is fake and staged. But it’s creating an act of illusion to make you interpret the film as real. You know what you’re seeing is actors on a set but you’re fooled into investing your own emotions into them. Tokyo Strut boils down this specific aspect of film to its most bare essentials. It openly admits it’s trying to trick you, and then builds off that assumption.

As the film goes on, it starts playing with your brain’s ability to recognise images.

These shapes are so far removed from our idea of what a dog or a human is, so it raises the question, what’s left? And the only thing it can be is the rhythm. It’s taken all those living movements and transferred them onto simple lines. Tokyo Strut ends up personifying the rhythm that’s at the heart of the movie turning, it into a living, breathing creature. And it creates this incredible visual representation of what rhythm is. —Jai

Tokyo Girl (dir. Maho Shimao)

The looping animations superimposed on footage of city life in Tokyo Girl recall Muybridge motion studies in their satisfying brevity and iteration. They're basic units for Shimao to play with: there are often multiples of the same loop on screen, appearing at staggered times, from various angles, and/or with different paths/patterns of motion. Many are nudes, evoking a high art tradition—one that includes Muybridge—of the nude as an object for a disinterested (to a degree) aesthetic gaze. The copresence of the formal idealism of this gaze and the relaxed intimacy Shimao's nudes exude gives Tokyo Girl the charm of diary and fantasy both—a sketchbook quality; personal, but not reflexive.

The connection that the parallel planes of Tokyo Girl suggest between private imagination and urban rhythms seems, curiously enough, to point to a missing subject. While the title and opening shot (which shows two girls getting on their bicycles) conjure the thematic trope of "a girl, making it (or adrift) in the big city," all the subsequent footage is of traffic, without people in the foreground; no "girl in the city"—just the girl and the city. But the subject is, in fact, present: as the hand that draws, or the hand that holds the camera from inside a moving car. That space in between the parallel planes is, ultimately, one that Shimao reserves for herself. —Jinhyung Kim

Manipulated Man (dir. Atsushi Wada)

Manipulated Man's repetitive, meditative movement highlights the precise nature of the animation itself and heightens the oppressive tone of the subject. Atsushi Wada's color palettes are developed from the paper he draws on–washed, neutral beiges, browns, whites, yellows and grays add to the muted, simplistic style. His characters maneuver in a tempered, restrained manner, a purposeful smallness in their movement. They occupy little space (despite their rotund, bulbous faces) with thin outlines and most of the screen left blank, which creates a sense of inescapable obscurity. Accompanied by minimal sound, recurring breaths, knocks, and occasional tones from (what I assume is) a marimba create a rhythm. Struck by these distinct qualities while watching, I was lulled yet spellbound by a kind of muffled psychedelia. The manipulated man's mouth is opened and closed by another and he is saddled with three additional men attached horizontally, weighing his body. What emerges from his mouth when opened are other smaller men, birthed (fully grown and clothed) from his throat and spat out into the world to be controlled or perhaps to control, as they are dressed as the oppressor. A seemingly general meditation on censorship, lack of authority over one's own voice, or the pressure to conform in Japanese society. Will he ever escape? —Olivia Hunter Willke

Fishing Vine (dir. Mika Seike)

The cacophony of Fishing Vine is its greatest asset. Layers of textures —drawings, photographs, cutouts, leaves —intersect and interlace on the screen. Like Yamamura, her process of rendering still art into motion is laid bare as we see the frames shift from sequence to sequence. Seike’s texturally diverse style relates a parable-like fable about a man attempting to spy on a woman eating fruit from a tree through a small telescope. Yamamoto’s insistent clunking mechanical soundtrack thuds along, emphasizing his voyeuristic anxiety, before the woman makes eye contact with the spying man. The music ramps up here, and we are thrust into a series of fast-moving scenes where he attempts to climb one of the vines to reach her, only to find himself blocked by a crowd of identical men doing the same.

Seike’s usage of distancing through the abstraction of her character’s movements and the varying dimensional surfaces of her materials brings the story and its implications of feminism, surveillance, and futility into clear view. Her collage-like style provides a haunting intensity to every frame. When the woman looks at the voyeur directly, her flat facial expression and wooden movement cross into the uncanny valley, no doubt on purpose. We’re meant to be disturbed, because what’s going on and what she’s reacting to are disturbing. The man’s eventual rejection of this single-minded pursuit of her, after watching a bug cut off the vines which the lookalikes attempt to scale several times, results in the woman throwing fruit playfully at him, which grows into a tree of its own. Yet the narrative wraps around at the end, and we see another crowd of voyeur men with their own telescopes. The cycle of intrusion upon the woman’s peace and privacy continues, without a lesson learned. —Ryan Waller

Dog & Bone (dir. Kotobuki Shiriagari)

In 2004, a video was uploaded to the internet. The quality was low—it always was back then—pixels eating up the image into semi-abstracted digital noise. Uploaded by a teenager under the name SuperYoshi, it showed recorded footage of the Super Mario Bros Super Show, only something was wrong. The scenes were clipped and out of order, gags repeated ad nauseum and dialogue turned borderline incomprehensible. It was surreal and strange, like nothing else on the platform, and it wouldn't take long for it to change internet humor forever.

The video’s title was Recycled Koopah, and it was the world’s first YouTube Poop.

This didn’t come entirely out of nowhere—the late ‘90s and early ‘00s were a wild breeding ground for a very specific style of comedy, one that could only thrive in the lawless lands of the internet. Sites like Newgrounds and Albino Blacksheep propagated loud, extreme amateur flash animation, while boards like 4chan (shudder) developed a dense language of self-referential memes. It was a time of absurdism and nihilism, of wild zigs and even wilder zags.

Dog & Bone feels like it exists in that same world. A totally out-there mixed media animation from 2006 by Shiriagari Kotobuki, it is a short that thrives on nonsense, following a rotoscoped person with a real photo of a dog for a head walking through obstacles in a poorly sketched world of pencil. One after another, bizarre non-sequiturs rush past the screen: one moment the cut-out of a woman is dancing and shooting paper hearts at the dog-man, the next they are running into a movie ala Sherlock Jr. before being assaulted by missiles and wandering into live-action footage. It is weird and confounding and gleefully dumb. It is also, like YouTube Poops and so much of the internet’s bizarre humor, uproariously funny.

This shouldn’t be too surprising. Kotobuki has been a fixture of comedy manga since the late ‘80s, his fiendishly clever, gut-busting satires regularly appearing in transgressive, forward-thinking publications like Comic Beam and AX—places that pride themselves in side-stepping mainstream conventions and giving a home to modern hetauma.

There’s no fully agreed upon criteria for what makes something hetauma, but the basics are as simple as can be: it has to be bad but good (hetauma literally a portmanteau of Japanese words meaning bad and good). Whether that be on purpose or accident or simply thanks to a lack of formal training, hetauma challenges and defies the broadly accepted conventions for what makes art valuable. The artwork might be incredibly amateur, and the story might not follow any logical structure, but hetauma work transcends, revealing the futility of attempts to quantify art.

YouTube poops, then, are hetauma. Memes and internet comedy are hetauma, with their purposefully deep-fried .jpegs, audio peaks, and anti-joke punchlines. The world we live in now, the one shaped by the internet, is hetauma.

And so is Dog & Bone. It is a short that, for an international audience, has aged into itself, its Dadaist comedy stylings finally in step with the wider world. It’s stupid and dumb and makes perfect sense, because it understands the purpose and value of art in the way only hetauma can. Technical proficiency isn’t important. Complexity doesn’t matter. Art doesn't have to be “profound,” just like it doesn't have to be “moving,” or even “good.” It simply has to be.

What could be more valuable than that? —Baxter

Nuance (dir. Murata Tomoyasu)

Nuance taps into a feeling so simple, but one that I’ve struggled to put into words for years: life is too busy. The film starts by showing you all of these images of Tokyo, but they’re always rendered multiple times—in one scene, there’s a bunch of vehicles shown crossing the motorway, but they’re continuously redrawn with different art and different colours. Each frame is gone before you can even really pay attention to it, and it just blends into the next. It’s a very specific recreation of what it’s like to live in a city. You see all these stimuli flying by but you never stop to consider it.

Nuance really highlights how much we take for granted day-to-day. A city is a crazy thing to describe on paper. The idea to condense a large amount of people into a tiny urban environment is fundamentally absurd. Even from a plumbing perspective that sounds like a nightmare. You’d think under compressed conditions like that, it would force people together, but the opposite is true instead. You end up getting into fights because someone is walking slightly slower than you.

About halfway through Nuance, the city fades away completely, and we’re left with these drawings of people walking through pure black. They’re all ignoring each other and keeping to themselves and they’re all drawn as incredibly dull colours—greys, blues, browns. They’re all colours of isolation. It’s like the vibrancy of their life has been completely drained from their bodies. We get so used to living in our environments that the colour starts to fade.

At least to a certain degree, Nuance reminds me of how repetition and routine can dull down our senses if we don’t try to fight back against it. As we walk the same paths—take the same commute day-in day-out—we start to put up shields to protect us. There are times where I’ve rode the tube in London completely zoned out just waiting to get to my stop. In this weird zombie state, I can change tube lines, listen to music, and tap in and out at the station. During all of this, I never stop to consider what a miracle it is that I can do this. What keeps the cycle of the city running? What keeps me running?

I’m so focused on moving, and trying to get to the next destination, that I forget to enjoy my journey there. It’s like I’m chasing inertia itself. I never stop to smell the roses. Although to be fair, in London it’s more likely to be the smell of a festering rat carcass instead. —Jai

Hashimoto (dir. Taku Furukawa)

Four months ago, Youtube commenter @ArthurBecker-fc6ug watched Motione Lumine (1973) on YouTube. Released decades before Hashimoto (2006), Lumine is similarly abstract. The film consists of around 3 minutes of animated star clusters twisted into humanoid forms, galaxies and nebulas leaping through the vast emptiness of space over an unnerving synth soundtrack. It’s eerily gorgeous and genuinely impressive in how it manages to anthropomorphize handfuls of light.

I watched it alongside a few other of Furukawa’s shorts after watching Hashimoto. I loved it, to be honest. Here’s what our good friend Arthur thought:

This is one of my favorite YouTube comments of all time. Everything about it sings to me: The thought of some guy stumbling upon a 50-year-old Japanese avant-garde animated short film with barely 200 views, watching it in full, and then half-heartedly writing this in response has brought me ample joy since I made my discovery.

It’s also a good excuse to force myself to think about why I do like these films, and why I pestered my friends with a link to Coffee Break (1972) with no comment beyond “this kicks ass.” It’d be easy to just call Arthur a stupid moron who doesn’t get it. (Which, to be fair, Arthur is. Shut the fuck up, dude.) On the other hand, I find it really valuable to try and articulate what an experimental film does for you in response to a half-hearted dismissal like Arthur’s, even when you can’t clearly parse those feelings. Unlike narrative film, you can’t fall back on plot or character writing. You’re forced to try to boil down a very personal, sensory experience into something digestible.

After sitting with this for a bit, I came to this: Furukawa understands that animation doesn’t have rules. There are no sets or actors to lock in, no pesky rules of physical space to get in your way. It’s just what’s being drawn, and that can change at any moment. Throughout Hashimoto, the scratchy humanoids smoking in a train station explode into rats and crows at a moment’s notice, screaming at each other and ultimately killing (?) one person after combining into a spiky glob of ink. I love that glob of ink. It’s anarchic in the non-arguing-on-Twitter sense, bursting with energy and possibility. Coffee Break functions in the same way and is somehow even more chaotic, where every new sip of coffee reveals even a new suite of drawings and colors to luxuriate in.

I don’t know how you could watch Hashimoto or Coffee Break and not come to the conclusion that Furukawa loves this shit. There is a love and care for what animation can do, from the chaos of Hashimoto to the more sedate, contemplative Motion Lumine, which feels almost like an experiment in context—if I do this, will it work?

That makes all of Furukawa’s films engaging and straightforwardly fun to watch. It makes me happy to feel like I’m sharing in his love of the craft just by spending a few minutes with a work.

It’s nice ,i guess? —jeddy

Funkorogashi (dir. Yoji Kuri)

When I was a kid, my parents read me children's books in both Korean and English. One of the Korean books I remember best is one my dad liked reading to me, because it appealed to his scatological sense of humor: a mole wakes up one day to find resting atop his head a sculpture-perfect stool specimen which, to his chagrin, he cannot identify. The story consists of his going around to ask his animal friends, one by one, whether the stool is theirs; each, of course, helpfully provides their own stool as proof to the contrary, until the mystery finally resolves upon the mole's encounter with the culprit.

Funkorogashi—a short about dog poop, of all things—seems to tap into this specific sense of humor; the picture-book style of the animation, which relies on simple drawings and just a few alternating frames to express movement in most scenes, reinforces the association. The dogs here (and their owners) vary in color, shape, demeanor, and fashion in ways both comically apposite and (comically) not to their stool. I'm now slightly more convinced that "fecal typology" describes a microgenre of storytelling, derivative of the broader form of list-as-narrative-structure that prevails in children's literature—what easier way to teach the names of animals or colors, or the alphabet?

Given its unconcern for anatomical attention to detail, "Funkorogashi" isn't so didactic; nor does it have a mystery tying the plot together. Its focus is how dog shit imbricates a metropole: it violates the alleged propriety of the land of the bourgeoisie—a propriety their pets, of course, fail to recognize. As the film goes on, dog shit not only piles up on streets and lawns but gets onto plates, into beds, and atop heads, before agglomerating into a critical mass of cascading poop that swallows people whole. It possesses an insurgency that embodies the bourgeois nightmare of having to actually deal with the waste civilization produces—or rather, of finding ourselves without the marginalized labor and infrastructure that disappears that waste and makes our lives possible. Funkorogashi adds a dash of irony by revealing the bourgeoisie to lack the propriety their aversions are meant to show: in one scene, a woman hikes her skirt up to waist level (and panty visibility) to tiptoe through a field strewn with droppings. It's details like these that sharpen the edge of what are otherwise gross(ly entertaining) absurdities. —Jinhyung Kim

Yuki-chan (dir. Kei Oyama)

They wouldn’t let me through the doors, so the photo of her in the hospital bed was all I knew. Look closer: see a Kodak image of a blonde woman swallowed by a blossoming medical gown, grinding her teeth through discomfort to gleam a smile as a signal for her young son. Now a slow dissolve to the reverse side of those steel doors: check me out sitting in the lobby, a portrait of the author as a little squirt, flanked by my aunts and father, pawing that snapshot whenever I grow tired of re-reading my creased issues of Mad and Cracked in a pique of boredom mixed with incomprehension. My family had the photo rush-developed so I could still look at my mother while she was shut away from us during her extended medical stay. My consciousness as I understand it began somewhere around here; that picture of my mother lying prone in the clinic undergoing ureteroscopy both a first persistent memory as well as an induction in the ways of living and dying, of the fleeting distance between the two. Kei Oyama’s contribution to the Tokyo Loop omnibus, the animated short Yuki-chan, seeks to capture these sense memories associated with a child’s bewildering initial meeting with mortality.

At Yuki-chan’s outset, the audio track, conceived by Seiichi Yamamoto, hums with droning waves and the looping burbles of shuffling clicks and pops akin to the sound of Morse code. A little boy’s shadow is cast on the sidewalk, falling atop an earthworm bristling down the ground, the soundtrack mirroring the slow crawl. A mosquito lands on the boy’s hand; he crushes it, stares at the bug’s collapsed frame, then pokes the worm with a stick, lifting it for close study. A woman appears—a messenger from the adult world—and leads the boy’s hand inside the confines of a home where grown folks mill in stances of mourning and anticipation. Entering the next room, the boy meets a woman suspended in vigil over the pale corpse of a young girl, eyes bound by the telltale pockets of one who has wept severely. She speaks to the boy, though we do not hear her words, and caresses the forehead of the decedent before her. At the woman’s apparent urging, the boy does the same, his arm’s hesitant movement rhyming with the motions undertaken in the insects’ sidewalk world moments before. As the boy feels the girl’s forehead, he notices a weltering bite on his hand, a souvenir from the mosquito. Unexpectedly distracted, the boy prods at his sore and the scene ends.

Kei Oyama’s animations draw upon the fine grains of textures found upon gravel, upon the epidermis, from memories of Camille Pissarro’s canvases, from panes of machined glass—in Yuki-chan, the earthworm’s body is that of Oyama’s own skin scanned from his fingers, while the face of the dead girl who haunts the piece is crafted from his then-partner’s skin. In his work, we are in the presence of a sort of neo-impressionism wedded to a kind of covert scrapbooking; a suggestion of what unconscious autofiction may resemble. Yuki-chan presents a childhood cosmos rendered as pavement and domestic pathway, a liminal land drifting between comprehension and puzzlement, with the skittish movement of the figures and backgrounds here suggesting nothing so much as the blurred assemblage by which rods and cones of the human eye convert visual stimuli into significance.

If the pulsing movement of Yuki-chan’s animation reflects the process of seeing itself, that of information being decoded and understood, then the film itself provocatively seeks to trace the contours and outlines of formative memory. A single viewing of Yuki-chan was enough to excavate these buried early childhood memories of my earliest acquaintance with the stakes of death, of the senses imprinted upon that photograph of my mother in medical repose striking a hopeful stance for her son. One leaves this short work with awareness that the recall of memory is yet another hallway through which the visual excuses itself and meaning returns. It is to Yuki-chan’s esteemed credit that its halfway-excavated splinter of remembrance is a vivid meditation on the universal experience of youthful faculty without resorting to the cloying or traumatic. As with the photo of my mother in the hospital, the primal scene of Yuki-chan represents the necessarily limited scope of a child’s understanding and suggests that cinema may yet serve a similar role to the mosquito in drawing that which is nestled within closer to the surface. —Patrick Lynn Wilson

12 O’Clock (dir. Toshio Iwai)

An animator always needs to think about time. The illusion of animation hinges upon presenting a series of images in succession and fooling the viewer into believing there’s continuity between them. If they hit your eye too slowly, the trick doesn’t work and the result becomes a slide show. (And while slide shows, historically, have been used to connote continuity between still images, the invention of motion picture cameras made the magic lantern look primitive.) Rush through too quickly, and the suggestion of motion might still be believable, although it won’t feel natural. From one frame to the next, a decision must be made on the tempo the next image should be delivered. Modern cameras and computer timelines relieve artists of most of this pressure, but Toshio Iwai often chooses to make things difficult for himself by using the most primordial animation techniques.

Iwai’s first attempts at animation were hand drawn flipbooks, which require manually thumbing through every page to make the magic happen. Immediately, you’re forced to wrestle with the basic principles of the artform. Timing is limited by the speed you’re able to move the paper, associating each step with a physical property. Eventually, you might discover that smaller books flip more quickly and heavier paper is less inhibited by air resistance. To counteract the limitations of the object, you might learn to economize the use of your pages and intuit that certain crucial moments require more attention than the transitional points between them; you’ve independently discovered the concept of key frames and tweening. Doubtless, this instilled Iwai with an appreciation for pacing.

As his craft evolved, he gradually incorporated more computer technology into his work but kept pre-film techniques in his repertoire. His first art installation, Time Stratum I, projected the motion of hands and eyes with a reel of photographs printed on rolling cylinders. Its sequel, Time Stratum II, was a zoetrope of paper dolls endlessly dancing around a carousel as they spun on a rotating disk. For these to work, the speed and position of the objects needed to be meticulously calibrated so that the spell holds at any viewing angle.

In 12 O’Clock, Iwai returns to the methods that taught him how to make pictures come alive; he uses a series of phenakistiscopes—the first ever technique for simulating fluid motion—superimposed onto the face of an analog timekeeper. Like the zoetrope, a phenakistiscope takes advantage of the human eye’s tendency to focus on a singular position so that you see a procession of images in one place rather than a scatter of them in multiple locations. And because a phenakistiscope is flat, the illusion doesn’t break when it’s filmed—provided it’s captured at the correct framerate. As the clock’s second hand ticks to the 12 o’clock position, you hear that Seiichi Yamamoto’s score is perfectly synced to the rhythm of its real time ticking—and keeps step even as the hands begin to spin rapidly. Each full revolution of the minute hand marks a change in scene, with 60 minute intervals whizzing by in about 8 seconds. It’s a visual representation of the most fundamental tenet of animation and a reminder that, for Iwai, time is of the essence. —Shy Clara Thompson

Thanks for reading this tenth installment of once bitten, twice shy. Long time no see, yeah?

Huge thanks to my friends for graciously making the time to watch these films and share their thoughts. They’re all brilliant people, and I’ve shared links to their socials in their signatures. (Unless they didn’t want me to!) I’ve also decided to share some of their work at the bottom of the post, so please have a look if you want more things to check out. I’m endlessly inspired by the amazing things they do.

If you appreciate the newsletter, consider hitting the Ko-fi link below and donating. You can do it one time, or as a monthly membership if you really love me. I’ll see you next time. Thanks!

Blogroll

Baxter runs his own newsletter called Tsundoku Diving, covering cool esoteric Japanese media. He also regularly does his own translations of alternative manga and film, doing proper diligence and giving you the history.

Jai makes incredibly well-researched video essays about television and film on YouTube. After a year of plugging away, their channel has finally blown up with a wild retelling of the finale of Two and a Half Men.

Jinhyung Kim writes a quarterly column about the best sound poetry releases for Bandcamp Daily. I appreciate him being super tapped into this stuff because it makes life a lot easier for me.

Joshua Minsoo Kim runs the Tone Glow newsletter, which I also contribute to. He’s done hundreds of interviews with musicians and filmmakers and is one of the best doing it.

Shy Clara Thompson writes this very newsletter (hello!) and does culture writing in various places. Mostly recently, I put together a primer of ’70s Japanese folk and wrote an extensive guide to eccentric interpretations of Erik Satie for a neat little site called Shfl.

Ryan Waller runs their own newsletter called Vacant World, covering whatever fascinates them. I especially love their treatise on the state of modern hip-hop.

Olivia Hunter Willke writes about film and programs her own screenings in Chicago. Recently, she did an interview with filmmaker Joel Potrykus for Tone Glow.

P.S. Here are the albums I was listening to while doing the boring work of putting this post together:

Akiko Wada - Zenkyoku-shū ~ Datte Shōganai Jyanai (1989)

Bobby Hutcherson - Cirrus (1974)

Boris with Michio Kurihara - Cloud Chamber (2008)

Kuniharu Akiyama - Environmental Music for Dining Room of Athletes' Village in Tokyo Olympics 1964 (2016)

Always super interesting :)

An absolute pleasure to read, watch, and read again. Thanks so much for introducing me to such an interesting festival and an even more interesting discussion on the meaning and making-of and meaning-of-making-of animation. Always appreciate your writing!!