you only get one-shot: five short manga recommendations

In what felt like the worst month of my life, I kept it together by immersing myself in comics. Here's a small selection of what I've been reading.

Now more than ever, I find myself appreciative of the endless breadth of expression that can manifest in the totality of art. In the past, when I felt flattened by the weight of a world that only seems to get heavier—my spirit eroded under the onslaught of a raging wind that, in the moment, feels like it might never let up—my solution was to simply give up. I’d do nothing. I wouldn’t reach out to friends and attempt to stave off loneliness. I wouldn’t put on music to fill the vacuum of silence in my empty skull. I’d just seal my eyelids shut for as long as I could manage, trying my best not to let an errant beam of light convert into an electrical impulse. My lack of ability to form any kind of human connection in extreme emotional states, whether directly or through art, was alarming. I didn’t want to feel less like myself in the moments when my grasp on identity felt weakest—and so, I sought to level up my grip.

The risk of falling into a state of emotional comatose was high in the month of January. On the morning of the 13th, I received word of my dear friend Nicky passing away. While oscillating wildly through the various stages of grief throughout the day like my Kübler-Ross playlist had been put on shuffle, I was buffeted with additional news that my nephew and niece (ages 2 and 3, respectively) had also lost their lives. I shattered into a hundred thousand pieces. Without the support of some treasured companions who knew how devastating the loss of my fallen friend was—not only for us, but for the world—I may not have found the resolve to gather up those jagged fragments and start fitting them back together. The critical difference this time, I’m guessing, is that I couldn’t easily convince myself that nobody understood how I felt.

Remembering my friend’s passion for celebrating their favorite things prevented me from falling into another quiet repose. I spent the following week absorbing the words they left behind, desperately clutching the leftover warmth from a soul that burned hot so that mine wouldn’t go cold. Nicky loved manga, so I thought about manga. I flipped through the pages of things they loved; I revisited the things I wish I could have shared with them; and I took the plunge on things we were supposed to experience together.

In this exercise of silent remembrance, I made a useful discovery for myself: in the state I was in, manga was a good way to nurse myself back to health. Days felt longer and lonelier, but I felt more able to adapt to the dulled edge of my weather-beaten emotions by immersing myself in an art form that let me take it at a slower pace. The spaces between panels provided a comfortable place to camp when I felt at capacity. I often fell asleep with a book or tablet in hand, picking up where I left off when it felt safe to open my eyes again. Shorter stories affected me most strongly; I appreciated the ability to sip on a fully realized vision in short bursts, in the moments I was best primed to receive them. So here are five one-shots that reminded me how to access the depths of my own feelings.

I’m dealing with very short stories here, so it’s impossible to write about them without some degree of spoilers. If that bothers you, I encourage you to read them first! They all come with my highest recommendation.

Makimodoshi (Akino Kondoh, 2012)

It’s interesting to think about how personalized one’s relationships to physical space can be. Depending on where you were born and the type of architecture you’re most accustomed to seeing, you could be more or less responsive to certain optical stimuli. For example: one study has shown that people from India are more susceptible to the vertical-horizontal illusion, while a contrasting group from England were more likely to be fooled by the Müller-Lyer illusion.1 To narrow the scope further, another study showed that the indigenous Khoisan people of rural South Africa showed far less sensitivity to the Ames window illusion than those from more urban areas of the country.2 It would naturally stand to reason, then, that you could get more granular and still find significant variation—even on an individual level.

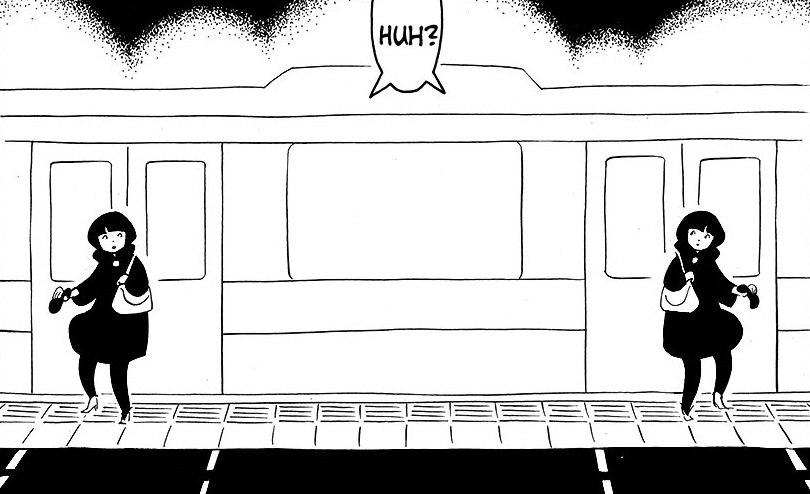

Akino Kondoh’s Makimodoshi (transl. “rewind”) gets me thinking about these individualized micro-spatial adaptations with its unorthodox flipped paneling. The protagonist examines two simultaneous lines of thought, trying to remember whether she went right or left while chasing down two identical looking people to return a mitten dropped on a train. Evaluating her thought experiment, she ponders the implications of a world that has abruptly flipped. All of a sudden, everything looks familiar but feels wrong; you have to be mindful of bonking your elbow against the wall while brushing your teeth, stretching your arm to your opposite side to scan your train pass, and which direction you need to twist a doorknob. The unsettling feeling of being in an unfamiliar situation is rarely so dramatic, but maybe it’s worth considering your biases and challenging them a little bit.

A Trip to Tynemouth (Hayao Miyazaki, 2006)

For someone with the stature of celebrated Studio Ghibli filmmaker Hayao Miyazaki, it can be difficult to imagine any opportunity being out of his reach. From his humble beginnings at Toei Animation in the early ‘60s, he’s done it all. He’s been able to bring some of his favorite stories to the big screen, building a grassroots venture between passionate friends into a media empire known to the entire world. But Miyazaki’s got unfulfilled dreams just like anyone else—heroes he wishes he could have met and places he wishes he could have gone. A Trip to Tynemouth shows a rare side of the old fogey, letting the whispers of his own heart grow a little bit louder.

Published in a Japanese edition of British author Robert Westall’s anthology of short stories, the manga is a partially autobiographical dramatization of Miyazaki’s relationship to Blackham’s Wimpy—a tale of rival Royal Air Force crews manning Vickers Wellington bomber planes. Perhaps because of the unusual nature of the comic as a companion piece to the short story, Miyazaki gets personal. He details his pilgrimage to the coastal town of Tynemouth in North East England where the story takes place, writes of his lifelong love of aviation with childlike excitement, and even fictionalizes a meeting with Westall himself. In typical Miyazaki fashion, he doesn’t allow the work to be too much about himself. He self-inserts as a cartoonish little pig, and takes long detours to describe the inner workings of aircrafts and scenes of war, but the imagined conversation with Westall reads loud and clear as his own internal dialogue—a conduit to explain the similarities he saw in the author despite being from countries that opposed each other in wartime. After all, who hasn’t done a mental rehearsal of what you’d say to your hero if you could meet them?

Pulp Girl (Youichi Abe, 2016)

I have no notes. It’s sick, it’s eight pages, there’s no dialogue. Just read it lol

Chirpy (Yoshiharu Tsuge, 1966)

I’ve been completely enraptured by the oeuvre of Yoshiharu Tsuge lately. The legendary manga artist, who got his start writing stories for kashi-hon rental comics in the 1950s, spent his entire career evaluating his relationship with storytelling. He honed his skills by borrowing heavily from his influences—even going as far, in one instance, to copy the composition of an entire page from Osamu Tezuka—but by the time he retired from manga was unshackled from established convention. His final efforts before putting down the pen in 1987 were works of warped surrealism and nakedly autobiographical confessionals that resembled little of what preceded them in manga’s then-young history.

But Tsuge’s transformation didn’t come from nowhere; he had like-minded contemporaries that pushed each other to evolve in the pages of Garo magazine, where its artists were given room to sharpen their craft with almost complete freedom from editorial oversight. Tsuge’s early stories in Garo, collected in the English language anthology The Swamp, track his stark shift in philosophy. His first, The Phony Warrior and Watermelon Sake, are Edo period tales of samurai that pick straight up from his kashi-hon days, but by the following year he was casting shades of the Tsuge that would change the landscape of alternative manga.

Chirpy is straightforward in its presentation, but unusual in its execution. It centers around a bar hostess and manga artist (a stand-in for Tsuge) down on their luck in modern Japan who decide to adopt a pet bird as a distraction from their financial woes. It manages to work as a temporary fix, but things fall apart when their avian friend unexpectedly meets its end. The story ends on a purposefully ambiguous and unsatisfying note, and was famously poorly received when it was published—perhaps because the manga-reading public wasn’t yet ready to confront that sort of discomfort with no help from the author. You don’t know if the couple turns out okay, and you’re not meant to. As a person that hinges a lot of my personal happiness on a pet that will only live a fraction as long as I will, it terrifies me; I can’t help thinking of my inevitable heartbreak.

The Real Momoka (Sumiko Arai, 2021)

There’s power in a name. Being addressed by the one you prefer can be intensely affirming, while being called something you don’t want to hear can make you feel like an alien in your own body. Even being called by a name you like can color your feelings about someone, depending on the amount of derision or affection you detect in their voice. “It suits you,” says one, but to another “it’s not what I expected.” Maybe your name was bestowed upon you by your parents, or maybe you took it upon yourself to veto their decision—but your relationship to your name is always in flux, at the mercy of whoever last let it part from their lips.

In The Real Momoka, the titular bartender has swapped names with her lover and regular patron, Makoto. The two of them are the only ones in on the secret. To the customers of the bar, “Makoto” is an appropriate name for a handsome woman with boyish charm, but Momoka is conflicted; she’s irritated how well her own name suits someone else, and feels frustrated that it only sounds good coming from someone she loves—but she’s unsure if those feelings are reciprocated. Makoto treats her delicately, the way she feels, rather than like a rough-and-tumble butch. It’s in those intimate moments that Momoka’s name truly feels like it belongs to her. It’s a potent metaphor for one of the reasons we chase after lasting romance: when someone makes you feel whole in a way nobody else does, it’s difficult to let them go.

I chose my name for myself. I’ve been using it ever since I was thirteen. I’ve had periods of being unsure if I’m truly who I say I am, but one thing has always been certain to me: my name sounds really good when someone I love says it to me.

Thank you for reading this second installment of my silly little newsletter. Getting this one out meant a lot to me, because I very nearly gave up on this creative venture and let it die on the vine. I’m glad I didn’t. I feel like I’ve accomplished a couple of important things. I’ve memorialized my friend Nicky in a way that makes sense to me, and my head feels clear in a way that it hasn’t since the day that I lost them. I followed through on something that’s strictly for myself, for once. And most importantly, I didn’t succumb to that ever-present desire to go into hiding just because things have been rough. Besides! I’ve got far too many good ideas to let them go to waste. I’m currently working on another one, so you can probably expect the next issue sooner rather than later.

If you’d like to donate, there’s a link below where you can do that. A couple of kind souls have done so already, despite the fact that I’m far too anxious to draw too much attention to the existence of the page. Whether you do or don’t, you have my thanks. I’m just happy that anybody wants to read what I’ve written.

By the way, you might have noticed the extremely adorable new icon at the top of the page. It was drawn by my friend BIG LOU. He’s amazing!! You should hit him up if you want someone to draw a funny guy for you.

Be safe. See you soon. I need a nap. Good night.

Segall, M. H., Campbell, D. T., & Herskovits, M. J. (1966). The influence of culture on visual perception. Bobbs-Merrill.

Allport, G. W., & Pettigrew, T. F. (1957). Cultural influence on the perception of movement: The trapezoidal illusion among Zulus. The Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 55(1), 104–113.