All You Need is Love: The Unlikely Friendship of Ryuichi Sakamoto and Kenichi Nishi

The story of what happened when a fledgling game developer and a vaunted musician combined their talents.

This piece was originally written for Lost in Cult’s Lock-On gaming journal, issue 003 of their print magazine. In light of Ryuichi Sakamoto’s recent passing, I’m sharing it here on my newsletter. I lived inside the universe of L.O.L. Lack of Love for a while, immersing myself in the game and poring over interviews so that I might understand the ways this work uniquely represents a meeting of two singular minds. Ryuichi Sakamoto and Kenichi Nichi met at a critical juncture, while both their creative lives were in a state of flux. Here’s the story of that fruitful friendship.

The creation of video games is often an intensive labor of love. Most people involved in their development, no matter how small the role they play, are usually eager to get into the details of their personal contribution—though that wasn’t always the case for Kenichi Nishi. Some of the most highly regarded and formative games in the genre of role-playing—namely, Super Mario RPG and Chrono Trigger—feature Nishi’s name as some of his earliest credits, but he’s not too keen on boasting about his time at Square. Asked about his role as a map planner on the titles in a 2006 interview with Cubed3, Nishi was quick to downplay his involvement. “I was rather a lazy employee who often did not show up to the office among the big team that consists of more than 100 people,” he said, continuing, “I think it is more appropriate for me to say I was more like pretending to be involved in the development.” He finishes with a laugh, but his answer speaks a solemn truth: he hadn’t yet found his place in the industry.

The tide would begin to turn for Nishi when he defected from Square in 1995 with aspirations to start his own studio. Inviting some of his closest friends that he made while at the company, the newly minted venture would be known as Love-de-Lic—a reference to one of Nishi’s favourite albums, the fifth release by electronic music pioneers Yellow Magic Orchestra, Technodelic. The working environment at Love-de-Lic, which had thirteen employees at its peak, was significantly different. Yoshiro Kimura—who contributed map and combat design to Romancing SaGa 2 and 3 while at Square—recalls it being a strange place to work, though that strangeness would elevate the collective creativity. “It was like a band playing an ad-lib session, with ideas flowing freely from every direction,” Kimura told Vice in 2020. “There was no ‘band leader’—we each respected one another, and we could express ourselves individually.”

To say that Love-de-Lic’s freewheeling atmosphere would leave a lasting impression on its staff is an understatement. In an interview for The Untold History of Japanese Game Developers book sometime in the mid-2010s—long after the studio’s dissolution in 2000—Kimura was still able to sketch the office floor plan from memory. He recalled playing GoldenEye 007 and StarFox 64 in a communal recreation room with coworkers, eating dinner made by the company’s manager with everyone almost daily, and even the positions of each employee’s desk, which were pushed closely together to encourage conversation while working. “Like we’re a big family,” he said.

Love-de-Lic’s environment of creative freedom would be immediately apparent from their first project, the self-described ‘anti-RPG’ called moon, released in 1997 for the PlayStation. Drawing from the team’s collective experience working on role-playing games with Square, they aimed to create a subversive take on the genre that was informed by a love for what brought them together and a desire to see it from a new perspective. Moon puts the player in the role of a ‘supporting’ character in a typical RPG, allowing you to bear secondhand witness to the deeds of the archetypal ‘hero’—a nakedly apparent reference to the protagonist of Dragon Quest. The hero slays innocent creatures for experience, barges into houses, and causes disruption to the lives of the townsfolk, leaving the player to deal with the aftermath. By observing the NPCs and helping them with their everyday lives, as well as bringing peace to the souls of monsters felled by the hero, you gain love instead of levels (a concept that inspired Toby Fox to explore similar themes in Undertale).

It’s crucially important to note that moon was not meant to be a criticism of RPGs, but a loving send-up; Nishi’s favorite game, at the time, was 1988’s Dragon Quest III. Love-de-Lic’s status as a group of people in comparatively minor, but nevertheless important, roles creating games that would crystallize the design language of a genre for years to come made them perhaps the most qualified to turn it on its head. They had firsthand experience, but were still on the fringes, appreciative of where they’d come from but unbound by fealty to convention. Though Nishi would describe his next project with Love-de-Lic as an RPG, it would be even more decoupled from any recognizable tradition. For L.O.L.: Lack of Love, the studio’s swan song released in 2000 for the Sega Dreamcast, Nishi followed his heart.

To hear Nishi tell it, Lack of Love began with a chance encounter with one of his creative muses—none other than Ryuichi Sakamoto, keyboardist of Yellow Magic Orchestra. A mutual friend of the musician and the game developer told Nishi that Sakamoto would be coming to the legendary Club Eden, and that they could be introduced. Nishi dropped everything on his docket to make the meeting happen. Nishi and Sakamoto hit it off instantly, discussing shared interests in video games, film, music, and computers. They exchanged email addresses to keep in contact, and while writing back and forth discovered another significant point of overlap: a deep concern for the planet’s environment.

Sakamoto’s life had been tracking along a parallel path to Nishi, striking out in his own creative direction after parting ways with Yellow Magic Orchestra. From an origin point of arcade game influenced techno with the band that brought him fame, he dabbled in classical piano, experimental electronics, and scores for film. By the time the two creatives met, Sakamoto had surrendered himself to the melancholy of Baroque-style chamber music, a reflection of his worsening view of the state of the planet. “The sadness comes from my concern about life,” he explained in 2019 to 52 Insights. “I knew that the world would become disastrous with environmental problems. I decided to speak out about that in the late ‘90s and a lot of fans thought I was mad.” Sakamoto famously said, after a visit to the nuclear disaster site at Fukushima, that “a tsunami acts almost as a state of restoration, trying to get back to its original state.” His belief was that the Earth would reach a state of equilibrium, if allowed to play out its natural course.

Nishi did not think Sakamoto was mad. The topic of environmental scientist James Lovelock’s Gaia Hypothesis—which posits that the Earth possesses a natural ability to self-regulate—came up in the email discussions, and Sakamoto floated the idea of making a game about it. Nishi couldn’t possibly turn down the opportunity to work with one of his greatest influences on a subject so close to his heart; he had the concept for his next project. Development began in earnest in 1998, with Nishi and Sakamoto brainstorming ideas through regular correspondence. The game’s title was a suggestion from Sakamoto, alluding to the dangers of environmental negligence. “We wanted to question the way in which our lifestyle lacks love,” Nishi told Retro magazine in 2010.

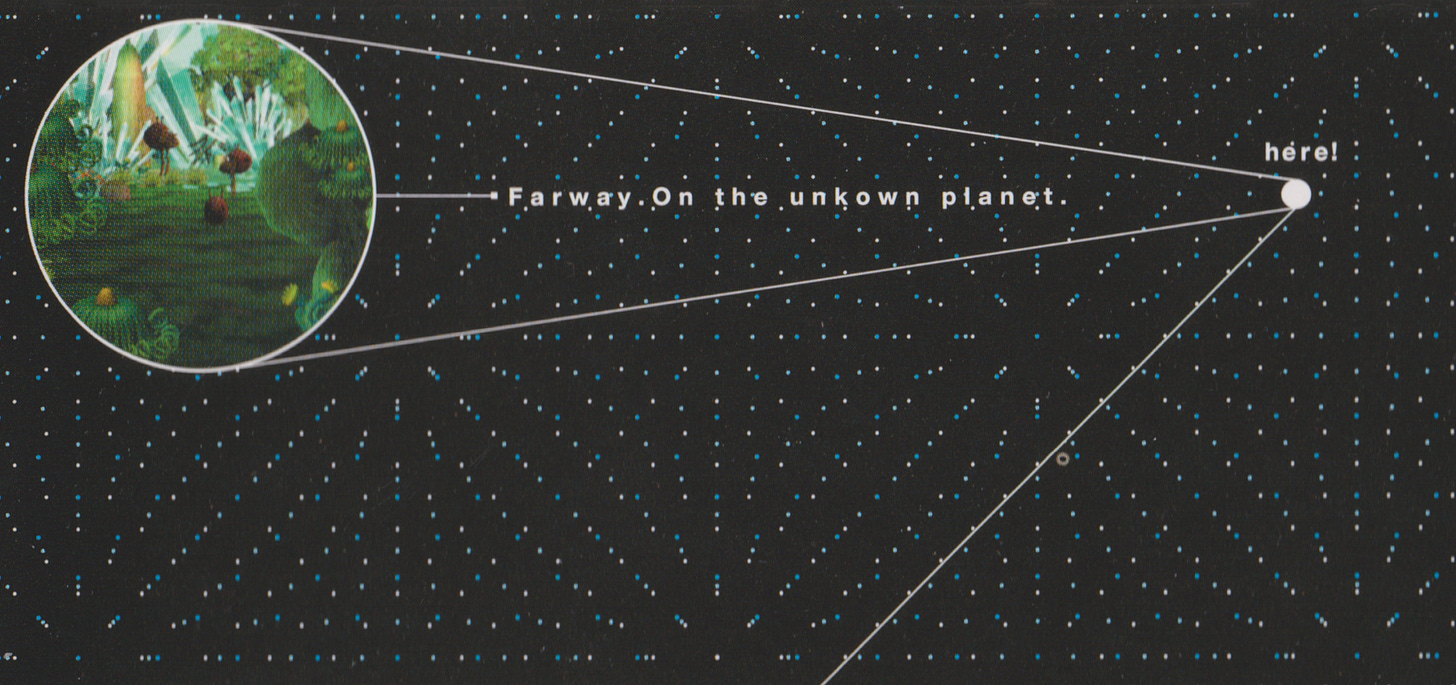

Like moon, Lack of Love plays with your expectations from the outset, introducing you to the Lack of Love Project, a program devised by humans seeking to find other planets so that they can terraform and populate them. A robot called Halumi is dispatched to the planet where the game’s setting takes place to carry out this task, and at first it seems like the cute little automaton might be the protagonist. As Halumi unleashes a torrent of machines from his spacecraft to get to work on the planet, control is given to the player and you discover that you’ll be playing the role of a microscopic organism trying to find a way to survive on this planet now under foreign duress.

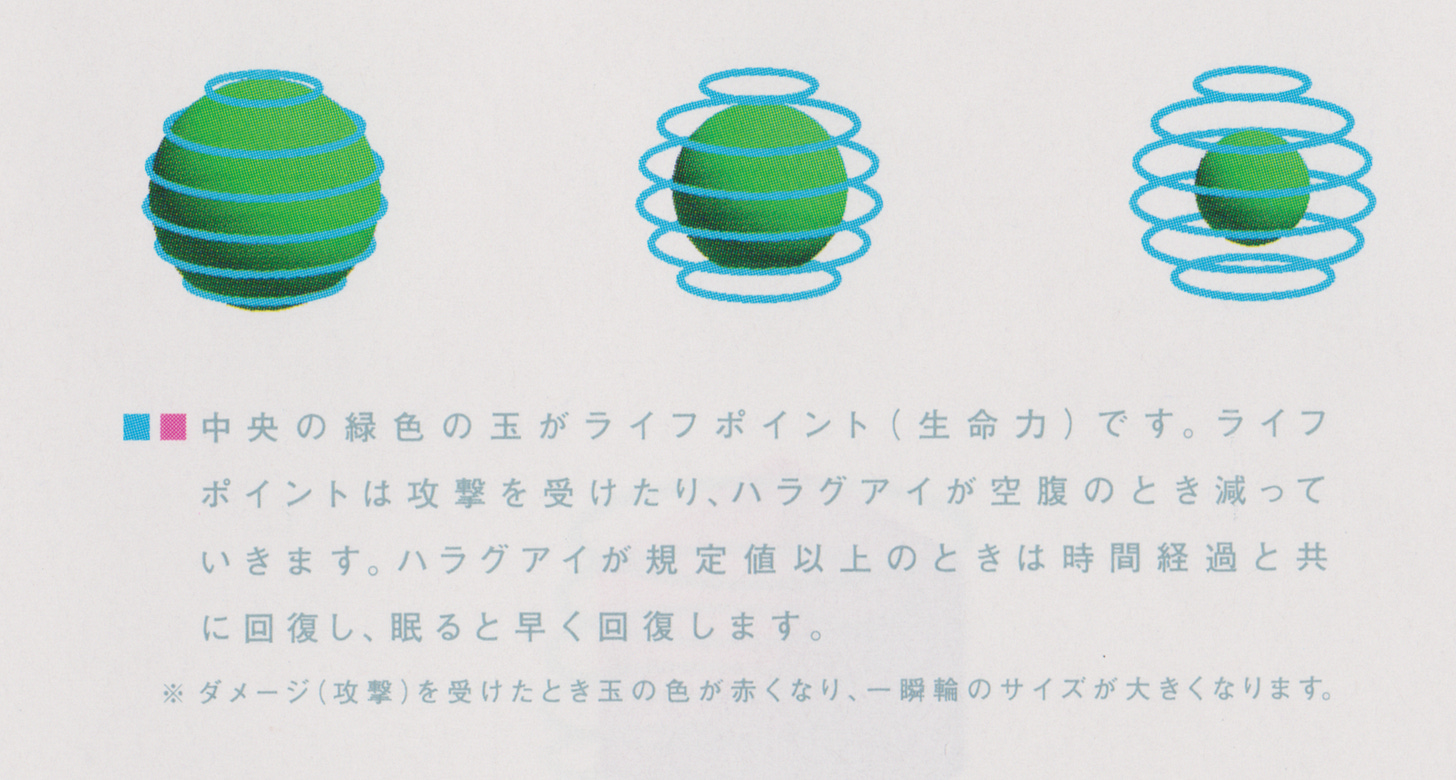

As you progress through the game, the creature grows and evolves in unexpected ways, and as it becomes more capable, it gains the ability to assist other creatures. (One stage of evolution is a black and white puppy-like form—a reference to Nishi’s dog Tao, whom he finds a way to slip into all of his games.) The game contains no dialogue or text, leaving only audio and visual cues to determine how best to elevate one another against a common threat. It acts as a potent metaphor for the fight against ecological harm, where the solutions aren’t easy and there is a need to reconcile differences in everyone’s needs—human or not—for the good of all the planet’s inhabitants. Sakamoto’s soundtrack, used sparingly to punctuate the most emotional moments in Nishi’s writing, channels the aching sadness of their environmental angst to underscore feelings of loneliness and a longing for togetherness.

Each game in Love-de-Lic’s repertoire exposes the bleeding hearts of the human beings that created them, and expresses a deep affection for something or someone. In the case of Lack of Love, it shows that one can gain fulfillment from finding common ground with others in ways you never considered. Working toward a future you’ve never known—whether that’s environmental prosperity or anything else your heart yearns for—starts to make sense because, through forging connections, you’ve finally learned it’s possible. Or, to put it another way: if it hurts, that means it can heal. ✿

Thank you for reading the fourth installment of once bitten, twice shy. I wrote this piece before many were expecting the untimely passing of Ryuichi Sakamoto, but I put a lot of heart into it and I remain proud of what I’ve written. Sakamoto, along with his friends and collaborators in and around Yellow Magic Orchestra, are responsible for nurturing my curiosity for almost everything I love. They each spread out into wildly unique paths, touching every form of art with unrestrained creativity and zero care for convention. I hope to evolve into a similar fearlessness.

In the meantime, while I gestate in my chrysalis, I will simply pay forward my gratitude. Rest in peace to both Ryuichi Sakamoto and the late Yukihiro Takahashi. I lay a thousand flowers at your feet.

Wonderful piece!